Five years ago – almost to the day – I came to The Hague for the very first time to attend a brilliant and, in hindsight, life and sanity saving seminar on RSI. An article about it followed, and it started with this line:

“Exactly two weeks ago I found myself, for the first time in my life, stepping off the plane in Amsterdam, and going, also for the first time in my life, to The Hague.”

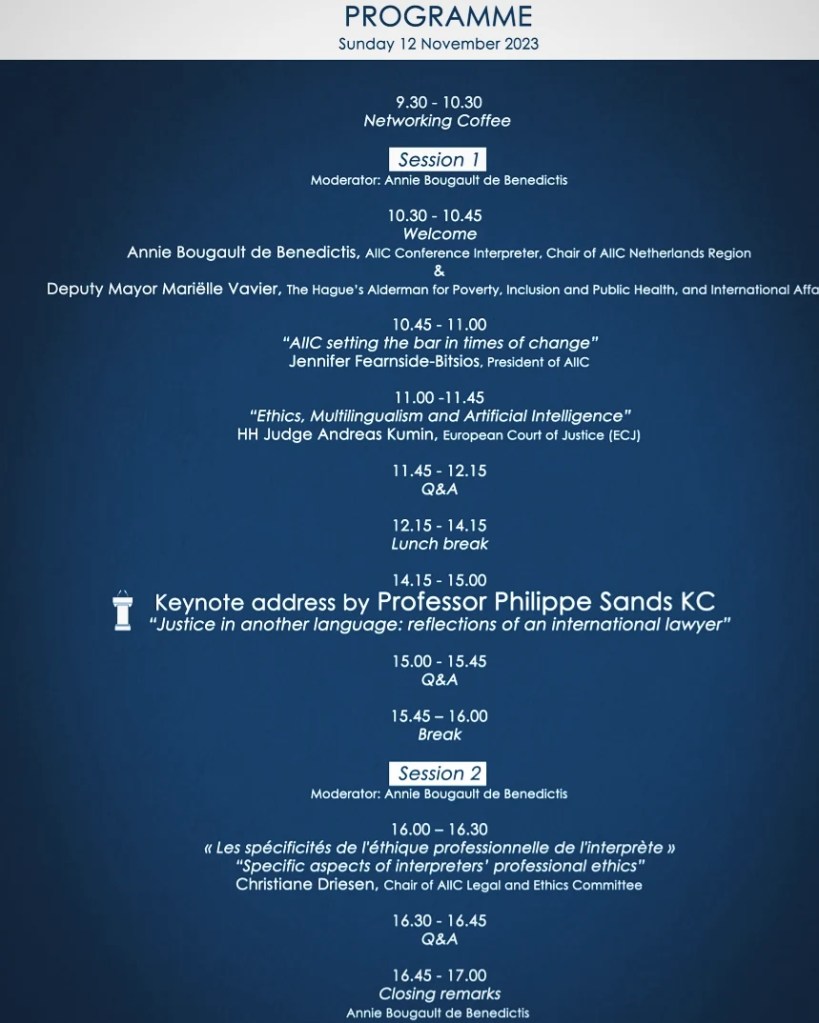

Now, returning home to Strasbourg from yet another work stint in The Hague, exactly two weeks after the latest edition of the AIIC Netherlands Legal Symposium, I couldn’t help but look back at that post from five years ago.

How much the world has changed in that short space of time… and the interpreting world with it. I still remember the hypothetical terms we used to talk about distance interpreting back in the day. And I am still immensely grateful to the organisers for putting together such a good panel, and for kicking off the debate.

Just as I am grateful for the topic of this year’s edition of the AIIC Netherlands Legal Symposium, because now, perhaps more than ever before, the question of ethics is one we cannot afford to ignore.

Colleagues from AIIC Netherlands rose beautifully to the challenge. For they managed, once again, to put together a truly remarkable panel, with representatives of the two professions not only present, but also willing to share their knowledge and experience.

The result? A resounding success, an insightful and thought-provoking discussion bridging the gap between the legal and the interpreting worlds. It is one thing knowing that there must be much the two have in common. It is a completely different experience seeing just how much.

From acquiring new skills, to adapting to different environments (and legal systems), to navigating the myriad of ethical and professional dilemmas we all come to face… it seemed we covered every subject that came to mind, and more.

And if certain aspects seemed self-evident, it was valuable to look at them from a different angle. CPD, professional attitudes, and attention to context and detail – these are only a few of examples.

The big thing that is in common for us – judges and counsel – is that both ethically and professionally we need to know how to adapt.

Judge Guénaël Mettraux, Kosovo Specialist Chambers, formerly at ICTY

Judge Guénaël Mettraux then went on to illustrate this need to adapt – sometime an “ablation”, sometimes a “graft” – by drawing from differences between common and civil law jurisdictions. I was particularly fascinated by one such example, from the early days of international justice. Bowing to the judge (or judges), an obvious attribute of some systems, was apparently an inconceivable act of subjugation for others.

It was also interesting to learn that, despite international justice slowly veering from the Anglo-Saxon tradition to the practices of civil law systems, some traits of the former remain.

When we talk about professional ethics we also – inevitably – talk about loyalty, trust, and consequences.

We are there not only to serve the needs of the client who hires us, but the system of justice.

Professor Philippe Sands KC

It is equally important to be mindful of consequences, should something go wrong. Depending on your role (in the legal world) they may not be the same. For defence counsel, for instance, the consequences of a breach of ethical obligations will, in the overwhelming majority of cases, be borne by the client. If you’re the Judge, it is the process that will suffer.

Which is why self-regulating is so important to the process, and that of interpreting as well. And which is why the fact that we – in AIIC – have our very own Code of Professional Ethics is paramount.

To quote Philip Minns (AIIC) the three main challenges that conference interpreters are likely to face throughout their professional careers are “accuracy, confidentiality and your personal position”. If you are reading this and happen to be a conference interpreter, you’ve probably seen the first three articles of the AIIC Code of Professional Ethics more than a few times.

Article 1: Professionalism

Members of the Association shall not accept any assignment for which they are not qualified. Acceptance of an assignment shall imply a moral undertaking on the member’s part to work with all due professionalism.

Article 2: Confidentiality

Members of the Association shall be bound by the strictest secrecy, which must be observed towards all persons and with regard to all information disclosed in the course of the practice of the profession at any gathering not open to the public.

Article 3: Integrity

Members of the Association shall refrain from deriving any personal gain whatsoever from confidential information they may have acquired in the exercise of their duties as conference interpreters.

The Code has proven to be a useful tool, and continues to be relevant today, especially when it comes to matters of integrity and confidentiality. As Kate Davies, who is not only a seasoned AIIC interpreter, but also an experienced interpreter trainer, so justly put it,

We need to be extremely cautious – and very conscious – about putting ourselves out there.

And that is especially true today, when the pressure from social media feels so real, and ever-growing.

And then there is the question of the statute of limitations. Does it exist for lawyers, for attorney-client privilege? Does it exist for interpreters?

It was interesting to look at our Code of Professional Ethics in more detail – thank you Christiane Driesen (AIIC) for taking the time – and to compare it to some of the other Codes of Ethics and Codes of Professional Conduct out there (EULITA, AUSIT, NAJIT, SFT, to name a few, as well as several examples from other walks of life). It is true that many of the best practices stem from what we learn as children from our parents, our teachers, and our peers.

That moral compass is everything. But it is not always enough. And a deep dive into the history of canons of judicial and professional ethics also proved highly instructive, with references to the Bangalore Principles (2002) and the Codes of Conduct of different present-day courts and tribunals, and all the way to David C. Hoffman’s Fifty Resolutions in Regard to Professional Deportment (1836), George Sharswood’s Essay on Professional Ethics (originally published in 1849), and one of the first ever Codes of Ethics for judges – formulated at the end of the 19th century in Alabama.

The first Code of Legal Ethics in the United States, formulated and adopted by the Alabama State Bar Association in 1887 (and published two years later, in 1889), was later adopted, with only minor changes, by Georgia, Virginia, Michigan, Colorado, North Carolina, Wisconsin, West Virginia, Maryland, Kentucky and Missouri, in the years between 1887 and 1906, and finally by the American Bar Association in 1908, making it one of the landmark documents in the field.

The problem with most codes formulated and adopted in the century that followed is their lack of precision, and most of the panellists deplored the abundance of “grey area” in the existing texts. Just compare the more than 500 in John Wesley Hall Jr.’s Professional Responsibility in Criminal Defense Practice, and the ten to fifteen pages that make up the Codes of Conduct of some present-day international Courts and Tribunals. Oddly enough, the two “original” international tribunals, Tokyo and Nuremberg, had none.

Here as well, as Michael G. Karnavas, a Criminal Defence Lawyer invited to speak at the Legal Symposium, pointed out, we can observe the differences between the common law approach, which is to be more specific, almost legislative, and the more aspirational approach of civil law systems.

Which lead him to conclude that:

Legal ethics properly applied and understood is more than just a code of ethics.

The same goes for the interpreting profession and the way interpreting is used to ensure justice it served. The attention to detail is key. Neutrality is essential. And access to interpreting is of tantamount importance. And even if someone speaks 85% English, you cannot give them 85% of due process.

We all know of (many) unfortunate examples where that was not the case. But it is better to know of them and work on combatting such practises than pretend they do not exist. And that is also why continuous learning, hailed by Judge Guénaël Mettraux and our very own Kate Davies, is crucial both for individual development, and for the betterment of the profession. It is also what makes events such as this one so valuable.

Independence, impartiality, integrity, propriety, equality, competence and diligence are featured in most codes out there, from the Bangalore Principles of Judicial Conduct (incidentally, a mere eight pages, if you don’t count the short explanatory note) to the codes of professional translators’ and interpreters’ associations.

It is the implementation of these principles that is often more complicated than it would seem.

As Judge Joanna Korner CMG KC put it,

Justice must not only be done, it must also be seen to be done.

And even an appearance of bias may be dangerous, and constitute a challenge.

Judge Joanna Korner also reiterated the need for training that interpreters should offer to counsel and judges. Such training should cover how they work and the language they use in court – British lawyers especially being guilty of reverting to wildly idiomatic expressions too often for the interpreters’ ease and comfort. She also praised the interpreters she’s worked with – notably at the International Criminal Tribunal for the former Yugoslavia (ICTY) – for being able to give “not only the meaning, but also the emotion“.

Thomas Hannis, a Criminal Defence Lawyer, formerly at ICTY and STL (Special Tribunal for Lebanon), spoke of his “great like and respect for interpreters”, and Michael G. Karnavas also hailed the interpreters as “the unsung heroes” of the international justice system. High praise, and one that it took several generations of conference interpreters to earn.

As he wrote in his follow-up post,

Through the interpreter serving both as code-breaker and conduit, a speaker utters in one language and other language(s) are magically heard. Strange sounds converted into lucid, intelligible, discernible language, enabling discourse, exchanges, and action. But for the interpreters, none of this would be possible. Ditto for the translators who toil in the backroom turning the inaccessible into the accessible for the monoglots or linguistically challenged.

This appreciation didn’t always exist, and it comes from decades of hard work. Even though most speakers, like Judge Andreas Kumin from the European Court of Justice (ECJ), when asked, said that it wouldn’t ever occur to them to not trust their interpreters, it is not something to take for granted. To quote Professor Philippe Sands KC,

Trust takes time. And with interpreters it’s the same.

This trust isn’t something to be taken lightly, especially not with the pressures and challenges brought on by AI looming over us.

Our colleague Monika Kokoszycka (from the AIIC UK & Ireland Region) gave an excellent presentation to that effect, focusing on the challenges of new technologies, their limitations, and what it means for us as members of the interpreting profession.

It may seem exciting, and if you go to the trouble of testing some of the new tools out there, it really is. But there are also some major concerns regarding, among other things, data protection and intellectual property, the differences between high and low-resource languages, and the overall humanity of the process.

To quote Eliane Esther Bots from The New Yorker Documentary, In Flow of Words: Translating the Trauma of War:

With my voice and choice of words, I can make any sentence less of a confrontation, while still giving a correct interpretation.

There may be situations where “language access might trump all other considerations”. There may be scenarios where a poor machine translation might seem – or be – better than no translation at all. But in most settings where interpretation is used the stakes tend to run high, and we should not be rushing to trust machines with matters of life and death.

The machines themselves are not operating with even a fraction of the quality they need to be able to do case work that’s acceptable for someone in a high-stakes situation.

Ariel Koren, Respond Crisis Translation

And if you consider that some governments use machines to treat asylum applications, you may wonder why it is that those brought before international courts and tribunals get better – human – services than those trying to escape the consequences of their actions.

As humans we understand emotions, we can navigate visual cues, context, and culture, we can decide when to correct an error, and, perhaps most importantly, we know what we don’t know.

That level of humanity and responsiveness is, for now, consistently unachievable.

Lauren Gunderson

That was another idea the panellists seemed to have no trouble agreeing on, and not simply because they thought that was what a room of conference interpreters, predominantly members of AIIC, wanted to hear. Professor Philippe Sands, for instance, when speaking of his work as an arbitrator noted that he came to particularly “appreciate the role of interpreters in contributing to the atmosphere of collegiality in the room”, noting their “incredibly central” role to the process.

And it just may be that as human interpreters we are not competing with AI, but with what our customers and clients think AI can do for them.

One of the biggest harms of large language models is caused by claiming that LLMs have ‘human-competitive intelligence’.

Timnit Gebru

And here again it was striking to learn that judges and lawyers have similar doubts and asking themselves very similar questions, as shared by Judge Andreas Kumin, who evoked just some of the risks that AI poses in the world of international justice:

Machines could invent jurisprudence that doesn’t exist.

Which means, once again, that you couldn’t trust these technologies, not yet at least, and not when the stakes are this high.

It was fascinating to see so many similarities in the debates currently raging in the legal and interpreting professions.

And don’t even get me started on the truly incredible venue.

And I am immensely grateful to the Organising Committee for putting together such a beautiful and enlightening event. Annie De Benedictis, Eva Bodor, Conference, Diplomatic and Legal Interpreter, Katia Bensaid, Véronique Chatterjee-Mars, Veronica Cioni, Zouchra Aikaterini Kasimova, Eva Laszlo-Herbert, MA, Sylvie Nossereau, Maja Popovic, THANK YOU.

One of the main conclusions that seemed to transpire from the debate, and resonated from one speaker to the other, was the importance of learning, and never tiring to ask – even the most uncomfortable of – questions.

As interpreters we never tire of talking about curiosity. Often, however, we mean it as it applies to the subject of our work or the identities of the speakers we interpret. It should also apply to the ethical dimension of what we do.

And that, probably, is as good place as any to stop and bow out.